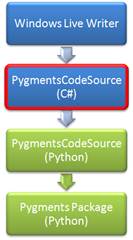

So I’ve compiled the Pygments package into a CLR

assembly

and loaded an embedded Python

script,

so now all that remains is calling into the functions in that embedded

Python script. Turns out, this is the easiest step so far.

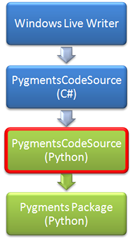

We’ll start with get_all_lexers and get_all_styles, since they’re

nearly identical. Both functions are called once on initialization, take

zero arguments and return a PythonGenerator (for you C# devs, a

PythonGenerator is kind of like the IEnumerable that gets created when

you yield return from a function). In fact, the only difference between

them is that get_all_styles returns a generator of simple strings,

while get_all_lexers returns a PythonTuple of the long name, a tuple

of aliases, a tuple of filename patterns and a tuple of mime types.

Here’s the implementation of Languages property:

PygmentLanguage[] _lanugages;

public PygmentLanguage[] Languages

{

get

{

if (_lanugages == null)

{

_init_thread.Join();

var f = _scope.GetVariable<PythonFunction>("get_all_lexers");

var r = (PythonGenerator)_engine.Operations.Invoke(f);

var lanugages_list = new List<PygmentLanguage>();

foreach (PythonTuple o in r)

{

lanugages_list.Add(new PygmentLanguage()

{

LongName = (string)o[0],

LookupName = (string)((PythonTuple)o[1])[0]

});

}

_lanugages = lanugages_list.ToArray();

}

return _lanugages;

}

}

If you recall from my last post, I initialized the _scope on a

background thread, so I first have to wait for the thread to complete.

If I was using C# 4.0, I’d simply be able to run

_scope.get_all_lexers, but since I’m not I have to manually reach

into the _scope and retrieve the get_all_lexers function via the

GetVariable method. I can’t invoke the PythonFunction directly from C#,

instead I have to use the Invoke method that hangs off

_engine.Operations. I cast the return value from Invoke to a

PythonGenerator and iterate over it to populate the array of languages.

If you’re working with dynamic languages from C#, the

ObjectOperations

instance than hangs off the ScriptEngine instance is amazingly useful.

Dynamic objects can participate in a powerful but somewhat complex

protocol for binding a wide variety of dynamic operation types. The

DynamicMetaObject

class supports twelve different Bind operations. But the

DynamicMetaObject binder methods are designed to be used by language

implementors. The ObjectOperations class lets you invoke them fairly

easily from a higher level of abstraction.

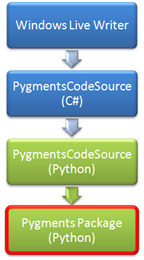

The last Python function I call from C# is generate_html. Unlike

get_all_lexers, generate_html takes three parameters and can be

called multiple times. The Invoke method has a params argument so it can

accept any number of additional parameters, but when I tried to call it

I got a NotImplemented exception. It turns out that Invoke currently

throws NotImplemented if it receives more than 2 parameters. Yes, we

realize that’s kinda broken and we are looking to fix it. However, it

turns out there’s another way that’s also more efficient for a function

like generate_html that we are likely to call more than once. Here’s my

implementation of GenerateHtml in C#.

Func<object, object, object, string> _generatehtml_function;

public string GenerateHtml(string code, string lexer, string style)

{

if (_generatehtml_function == null)

{

_init_thread.Join();

var f = _scope.GetVariable<PythonFunction>("generate_html");

_generatehtml_function = _engine.Operations.ConvertTo

<Func<object, object, object, string>>(f);

}

return _generatehtml_function(code, lexer, style);

}

Instead of calling Invoke, I convert the PythonFunction instance into a

delegate using Operations.ConvertTo which I then cache and call like any

other delegate from C#. Not only does Invoke fail for more than two

parameters, it creates a new dynamic call site every time it’s called.

Since get_all_lexers and get_all_styles are each only called once,

it’s no big deal. But you typically call generate_html multiple times

for a block of source code. Using ConvertTo generates a dynamic call

site as part of the delegate, so that’s more efficient than creating one

on every call.

The rest of the C# code is fairly pedestrian and has nothing to do with

IronPython, as all access to Python code is hidden behind GenerateHtml

as well as the Languages and Styles property.

So as I’ve shown in the last few posts, embedding IronPython inside a

C# application – even before we get the new dynamic functionality of

C# 4.0 – isn’t really all that hard. Of course, we’re always interested

in ways to make it easier. If you’ve got any questions or suggestions,

please feel free to leave a comment or drop me a line.