Now that I’ve introduced my simple hybrid GetThings

app,

we need to set about adding support for debugging just the IronPython

part of the app via the new lightweight debugging functionality we’re

introducing in 2.6. Note, the code is up on

github, but isn’t

going to exactly match what I show on the blog. Also, I have a post RC1

daily build of IronPython in the Externals

folder

since I discovered a few issues while building this sample that Dino had

to fix after RC1. Those assemblies will be updated as needed as the

sample progresses.

We saw last time how how easy it is to execute a Python script to

configure a C# app – only four lines of code. If we want to support

debugging, we need to add a fifth:

private void Window_Loaded(object sender, RoutedEventArgs e)

{

ScriptEngine engine = Python.CreateEngine();

engine.SetTrace(this.OnTraceback);

ScriptScope s = engine.CreateScope();

s.SetVariable("items", lbThings.Items);

engine.ExecuteFile("getthings.py", s);

}

You’ll notice the one new line – the call to engine.SetTrace. This is

actually an extension method – ScriptEngine is a DLR hosting API class

and but SetTrace is IronPython specific functionality . If you look

at the source of Python.SetTrace, you’ll see that it’s just a wrapper

around SysModule.settrace, but it avoids needing to get the engine’s

shared PythonContext yourself.

SetTrace takes a TracebackDelegate as a parameter. That delegate gets

registered as the global traceback handler for the Python engine (on

that thread, but we’ll ignore threading for now). Whenever that engine

enters a new scope (i.e. a new function), the IronPython runtime calls

into the global traceback handler. While the traceback handler runs,

execution of the python code in that engine is paused. When the

traceback handler returns, the engine resumes executing python code.

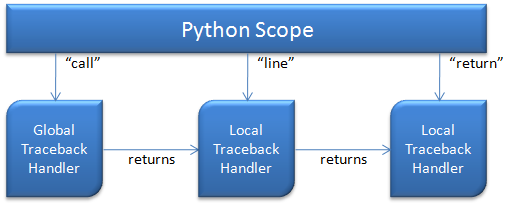

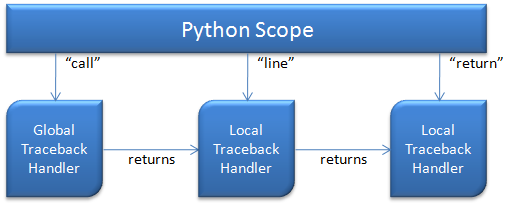

In addition to the global traceback handler, each scope has a local

traceback handler as well. The TracebackDelegate type returns a

TracebackDelegate which is used as the local traceback handler for the

next traceback event within that scope. Traceback handlers can return

themselves, some other TracebackDelegate, or null if they don’t want any

more traceback events for the current scope. It’s kinda confusing, so

here’s a picture:

You’ll notice three different traceback event types in the picture

above: call, line and return. Call indicates the start of a scope, and

is always invoked on the global traceback handler (i.e. the traceback

passed to SetTrace). Line indicates the Python engine is about to

execute a line of code and return indicates the end of a scopes

execution. As you can see, the runtime uses the return value of the

traceback for the next tracing call until the end of the scope. The

return value from the “return” event handler is ignored.

So now that we know the basics of traceback handlers, here’s a simple

TracebackDelegate that simply returns itself. The “Hello, world!” of

traceback debugging if you will.

private TracebackDelegate OnTraceback

(TraceBackFrame frame, string result, object payload)

{

return this.OnTraceback;

}

If you run this code, there will be no functional difference from the

code before you added the SetTrace call. That’s because we’re not doing

anything in the traceback handler. But if you run this in the debugger

with a breakpoint on this function, you’ll see that it gets called a

bunch of times. In the python code from the last

post,

there are three scopes – module scope, download_stuff function scope

and the get_nodes function scope. Each of those function scopes will

have a call and return event, plus a bunch of line events in between.

The parameters for TracebackDelegate are described in the Python

docs. The frame

parameter is the current stack frame – it has information about the

local and global variables, the code object currently executing, the

line number being executed and a pointer to the previous stack frame if

there is one. More information on code and frame objects is available in

the python data

model

(look for “internal types”). Result is the reason why the traceback

function is being called (in Python docs, it’s called “event” but that’s

a keyword in C#). IronPython supports four traceback results: “call”,

“line” and “return” as described above plus “exception” when an

exception is thrown. Finally, the payload value’s meaning depends on the

traceback result. For call and line, payload is null. For return,

payload is the value being returned from the function. For exception,

the payload is information about the exception and where it was thrown.

As I mentioned above, python code execution is paused while the

traceback handler executes and then continues when the traceback handler

returns. That means you need to block in that function if you want to

let the user interact with the debugger. For a console app like PDB, you

can do that with a single thread of execution easily enough. For a GUI

app like GetThings, that means running the debugger and debugee windows

on separate threads. And as I alluded to, tracing for Python script

engines is per thread. So next time, we’ll look deeper into how to use

multiple threads for lightweight debugging a hybrid app.